Front page

XML Feed

Read Our

"Love your site" -- Dan Savage

"A great read" -- Fareed Zakaria

"I enjoy OxBlog very much" -- Michael Barone

OxBlog: Trying to live up to the hype since April 23, 2002!

David Adesnik, a research analyst in Washington DC, received his doctorate in international relations from Oxford.

Email David

![]()

The Media:

NYT

WaPo

OpinionJournal

TNR

Weekly Standard

NRO

Slate

Commentary

BBC

Other Blogs We Like:

George Washington:

InstaPundit

James Wilson:

Brett Marston

Alexis de Tocqueville:

American Scene

Crescat Sententia

Crooked Timber

Galley Slaves

Eve Tushnet

Christopher Hitchens

Theodore Roosevelt:

Amygdala

Belgravia Dispatch

Phil Carter

Joyful Christian

Joe Gandelman

Adrianne Truett

Winds of Change

Pejman Yousefzadeh

Global Guerrillas

Calvin Coolidge:

ScrappleFace

Winston Churchill:

Sasha Castel

Andrew Sullivan

Tim Blair

Franklin Roosevelt:

Kevin Drum

Josh Marshall

Matt Yglesias

Democracy Arsenal

Dan Nexon

David Ben Gurion:

GedankenPundit

Kesher Talk

Friedrich Hayek:

Jane Galt

Virginia Postrel

Natalie Solent

VodkaPundit

Matt Welch

Ronald Reagan:

Power Line

RealClearPolitics

Worldwide Standard

RedState

Liz Mair

Daniel Patrick Moynihan:

Daniel Drezner

How Appealing

# Posted 5:24 PM by Ariel David Adesnik ![]()

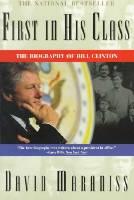

The book is superb. It is an insightful character study that asks and answers the question of who Bill Clinton is as a human being. In addition to interviewing hundreds of Clinton’s friends, colleagues and rivals, Maraniss has an unearthed a remarkable trove of letters written to and from Clinton during his formative years at Georgetown and Oxford.

The letters are so remarkable because they allow Maraniss to present Clinton both in his own voice and through the eyes of others, long before Clinton’s election as president had the chance to color the recollections of both his apologists and his critics.

In addition to being insightful, Maraniss’ biography is prescient. Although mostly sympathetic to the president, the author portrays Clinton as a pathological womanizer who cannot stop himself from going for yet another score even after his closest advisers – and the example of Gary Hart – made it painfully clear to the young governor that American voters demanded a certain amount of fidelity to traditional ethics.

But why bother reading or writing about Bill when Hillary is the Clinton that is poised to take the White House? Actually, I’m in the midst of reading Hillary’s autobiography and will report back on it soon.

But anyhow, who cares about Monica Lewinsky when there is a war going on in Iraq and we are still counting the dead in Mississippi and Louisiana? Well, my point wasn’t to write about Monica. Although I didn’t start reading First in His Class with any particular agenda in mind, I became increasingly curious as I read it about what lessons the Democratic party might learn from Clinton’s success as a candidate and (less consistently) as a president.

The fundamental question I wanted to ask was “What did Bill Clinton stand for?” Today, the Democratic party is so divided that it cannot present itself as tough on national security even though support for President Bush’s foreign policy is tenuous at best, in spite of OxBlog’s best efforts to explain the importance of winning the war in Iraq.

So what, if anything, did Clinton do differently? Was he able to win elections simply because national security was less salient in the 1990s? Or did Clinton represent a coherent worldview that commanded majority support among the voters?

Regretfully, I must report that First in His Class does not provide an answer to those questions. Nor is it particularly fair to expect that it should. As I mentioned above, the book is a character study. It is very tightly focused on Clinton’s personality. As a result, it says very little about his ideas and his politics.

For a brief period, during the era of the draft, politics were personal for Clinton and his friends. In his account of the era, Maraniss provides a superb portrayal of the restlessness that gripped those who sought both to come terms with the war in Vietnam as both a moral dilemma and a threat to their personal safety. Yet during Clinton’s career in Arkansas, politics was pretty much about politics (except perhaps when Hillary Rodham’s last name became a liability during Clinton’s fight for re-election).

Even though Clinton served for twelve years as governor, his exploits in Arkansas comprise just one third of Maraniss’ book. Compared to the extraordinary detail with which Maraniss renders Clinton’s development as a scholar and a politician in high school, at Georgetown and at Oxford, the author’s account of Clinton’s time in Arkansas is broadbrush at best.

To a certain extent, this approach makes sense in terms of writing a book about Clinton intended for a mass audience. Wonks aside, the human drama of Clinton’s years as a student makes for much better reading than discussion of his efforts to fix highways and raise revenue in Arkansas. However, the price of this decision is that it is quite hard to know exactly what Clinton stood for. Was he a moderate? A liberal? A centrist? A sell out? An ideologue?

As Maraniss tells it, one apparent theme of Clinton’s years as governor was his constant desire to be involved in some sort of grand project or crusade, whether for education or healthcare or better roads or whatever. As an activist who seemed to believe that bigger government (funded by bigger taxes) provided better answers, there was much about Clinton that comes off as “liberal”.

However, in the absence of greater detail, it is hard to be confident about such an assertion. Without a closer look at Clinton’s policy proposals, it is hard to know whether he was a real Great Society type or whether he understood that government works best when it helps citizens take the initiative on their own behalf and when it integrates the dynamics of the marketplace into the design of government programs.

With regard to tactics, Maraniss portrays Clinton as a ruthless practitioner of hardball. Memorably, Clinton often said that if someone tries to hit you over the head with a hammer, you should cut off their hand with a meat cleaver. Nonetheless, Maraniss never suggests that Clinton did anything particularly nasty or dishonest during his seven campaigns for governor of Arkansas. In that sense, Clinton comes off as a something of a John Kerry: intellectually aware of the importance of fighting fire with fire, but never cold-blooded enough to actually do it.

Yet again, the absence of detail renders this sort of conclusion tentative at best. Quite reasonably, Maraniss focuses on only two of Clinton’s seven campaigns. His book is long enough as is, amounting to almost 500 pages. Nonetheless, I would be very interested in reading a 500 page book devoted exclusively to Clinton’s time in Little Rock.

Bill Clinton is the only Democratic president since Franklin Roosevelt to win more than once at the polls. It is imperative to understand why, regardless of whether you are a Democrat planning on another resurgence or a Republican who wants to make sure that no such thing ever happens. (0) opinions -- Add your opinion